Walker Art Center: Preserving History, Art, and Conversations

Considered one of the nation’s leading art institutions, Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center has been a leader in musical and dance performances, contemporary design and fine arts, and cinema since 1940. BAVC Media’s Preservation Department has been collaborating with the Walker Art Library & Archives in recent years, digitizing selected one-of-kind videotapes showcasing just a sample of their extraordinary collection.

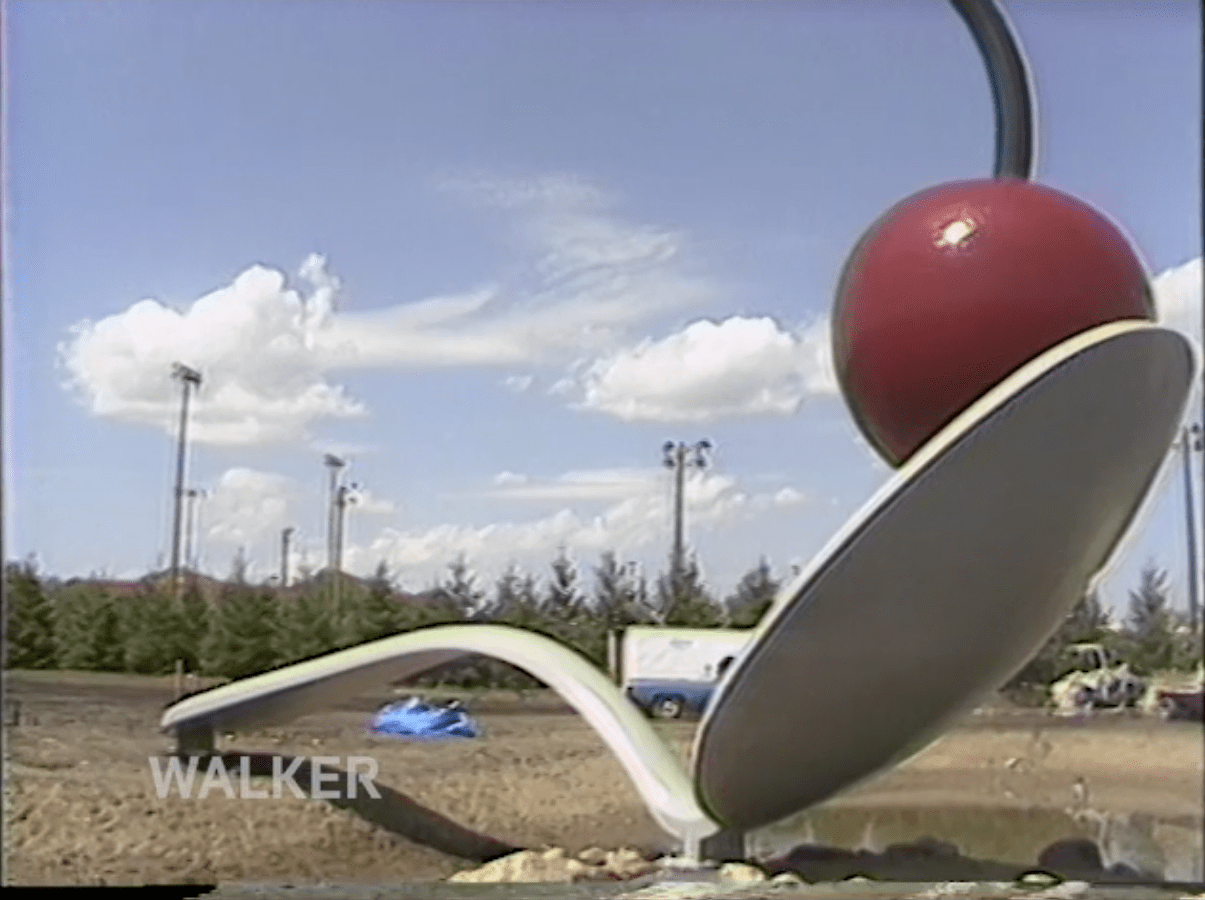

One of the more prominent works of art located in the Sculpture Garden in front of the Walker Art Center is Spoonbridge and Cherry. A whimsically large bent spoon arches over a man-made lake, balancing a large red cherry with its stem curving skyward. Known for their large-scale works of everyday objects, Claes Oldenburg and his wife, Coosje Van Bruggen, were commissioned by Walker to create this piece in 1985. Beginning in May of 1988, much of the installation was captured on several ¾” U-matic videotapes.

The series begins with this massive, odd-shaped wrapped object strapped to an arriving semitruck’s flatbed during a downpour. As the spoon becomes gradually unveiled, Oldenburg and Bruggen are seen wandering the muddy grounds with museum staff while a crew of men in hard hats lift and bolt this unique monstrosity into place. The team of workers scaling the spoon in order to complete the artists’ vision is a rare sight. A crane then slowly lowers the massive cherry onto the spoon. Applause is heard as the water sprays for the first time from the cherry’s stem, down the spoon’s bowl, and into the muddy lake-in-progress. Spoonbridge with Cherry smiles at museum visitors today.

[Video: Spoonbridge with Cherry installation at the Walker Art Center in 1988]

What makes this video footage significant is that the public are rarely present to witness the artists at work, rather we are invited to observe and/or critique the end result. Other U-matic videotapes in the collection feature David Hockney and museum curators brainstorming for his installation that would become Ravel’s Garden. Hockney’s knowledge of classical and opera music as well as his ability to intricately retell historical fables offer a small morsel of insight into his creative mind at work. Expounding his passion of what he paints aside, he has no difficulties captivating his listeners with what sounds like his own built-in iambic pentameter.

Another series of recordings invites us into an in-depth and personal conversation between notable film historian William K. Everson and filmmaker Michael Powell. Powell speaks openly about his experiences as a distinguished British director during WWII. His visionary skill has left a valuable imprint on cinematic history with Technicolor masterpieces such as Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes. Other recordings follow artist Nancy Graves as she touches up paint on one of her sculptures prior to her exhibit at the Walker. Jennifer Bartlett takes us on a tour around her boat-like sculptures, fences, and small houses which multiply like a small seaside town (realistically located in a studio space somewhere in the middle of bustling New York City). Then there’s that singular recording of William S. Burroughs, sitting center stage at a table in the Walker auditorium, reading his own short stories from a folder of loose papers to a fully-captivated audience. No frills and no additional decorum necessary; his words in his voice are an experience in and of itself!

There are dance performances, walks through the galleries with artists discussing everything from their inspirations to their chosen use of a particular medium, and video art pieces – intended only to be displayed on a screen.

All of these moments, like the installation of Spoonbridge with Cherry mentioned above, are rare recordings written into the millions of iron oxide particles on U-matic tapes. U-matic is a fragile and complex videotape format that has a shelf-life nearing expiration. It is the first video format to be housed in a cassette (prior formats were on open reels). U-matic earned its namesake based on the U-shaped curve the tape makes as it is extracted from its housing and wraps around the head drum for playback. Due to this complex and highly-technical threading pattern, the format was commonly utilized by professionals and did not last long on the consumer market.

[Video: u-matic tape path]

In BAVC Media’s Preservation department, the Walker Art Center’s collection is no more or less “at-risk” than other ¾” U-matic collections. We found that roughly one in every four tapes suffered from Soft Binder Syndrome (also called “sticky shed” or “binder hydrolysis”) which can make playability difficult, potentially causing damage to both the tape or the equipment. We mitigate this issue by baking the tape; actually placing it in a specialty pre-programmed oven which draws the unwelcomed moisture out of the tape. Delicate cleanings, not only of the tape itself, but of the tape’s path inside the deck and around the rotating head drum are essential to reduce dirt buildup. Any detritus passing by the heads on the drum can cause dropouts or complete image loss during the capture process.

As AV archivists and preservationists race to save these nearly-obsolete materials, taking the time to thoroughly inspect and take conservative measures ensures that these moments with Oldenberg and Van Bruggen, Burroughs, Hockney, or Powell can be revisited by anyone who enjoys spending as much time learning from them as I did.

Anne Marie Smatla is a Preservation Technician at BAVC Media.

The Bay Area Video Coalition is a non-profit and your support matters! You can contribute to BAVC Media’s educational programs, community media outreach, and future preservation work here. Donate $25 or more and receive one of our stylish enamel pins!